The End of Thurow

written by

Helene Berckemeyer, née Bock

(October 13, 1883 – March 30, 1966)

∘ ∘ ∘ ∘ ∘ ∘ ∘

German to English translation by Rita Stark, née Abel – Kaslo, B.C., Canada – March, 2003 with assistance from Alexander von Storch, Escondido, CA, USA

∘ ∘ ∘ ∘ ∘ ∘ ∘

A typed copy (in German) was made from the faded original in January 2001, by Alexander von Storch, Escondido, California, USA.

That copy was revised (in German) by Bernd Sasse, Rheinfelden, Switzerland.

The German to English translation was made from Bernd Sasse’s revision.

Helene Berckemeyer née Bock October 13, 1883 – March 30, 1966

Helene Berckemeyer née Bock October 13, 1883 – March 30, 1966

Bernhard Philipp Berckemeyer November 3, 1879 – January 27, 1962

Bernhard Philipp Berckemeyer November 3, 1879 – January 27, 1962

Groß Thurow – front of house

Groß Thurow – front of house

Groß Thurow – back of house and Kaffeehütte (coffee hut)

Groß Thurow – back of house and Kaffeehütte (coffee hut)

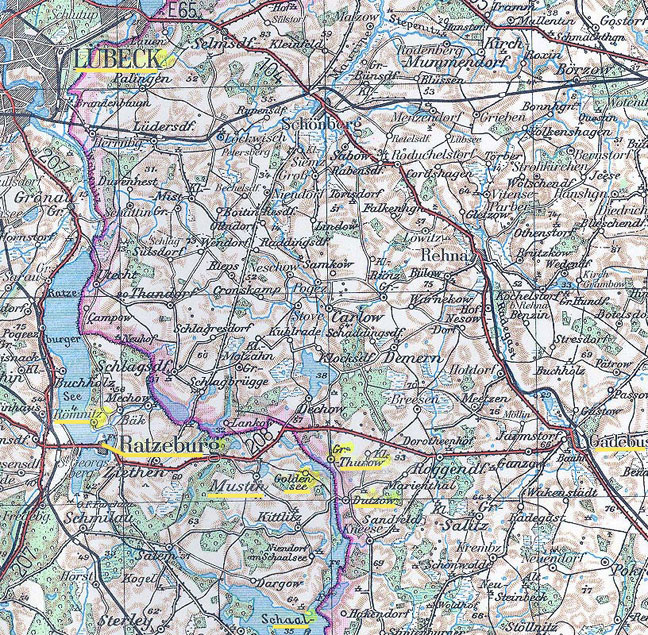

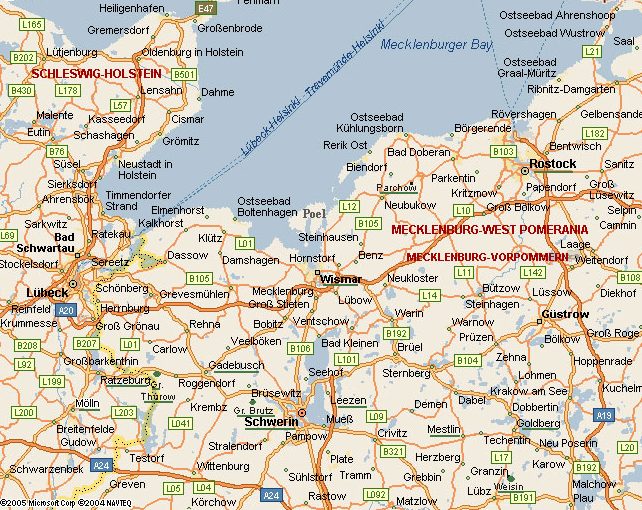

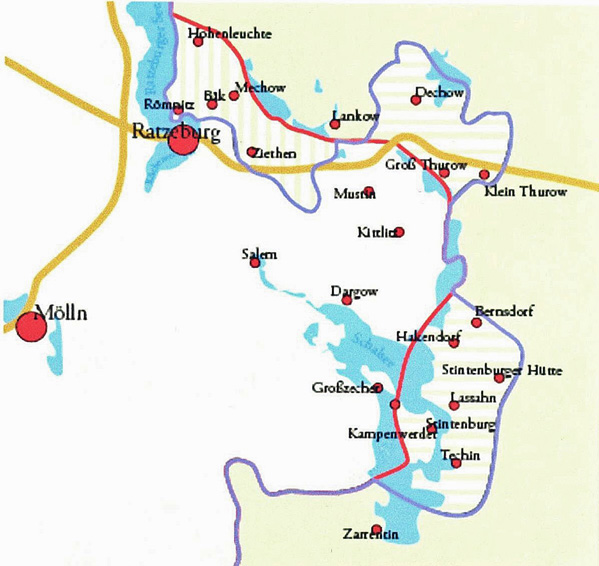

Römnitz, Ratzeburg, Mustin, Goldensee, Gross and Klein Thurow, Dutzow, Gadebusch, Schaalsee. [The pink line shows the border (after it was straightened) between the British Occupation Zone on the west and the Russian Occupation Zone on the east.]

Römnitz, Ratzeburg, Mustin, Goldensee, Gross and Klein Thurow, Dutzow, Gadebusch, Schaalsee. [The pink line shows the border (after it was straightened) between the British Occupation Zone on the west and the Russian Occupation Zone on the east.]

Treks 1945

February 1, 1945

At daybreak on a cold and foggy day; a grey, covered wagon train creeps over the long driveway toward the yard. We know what it signifies – the forerunners have told us of the misery that is nearing us from the east[1]. It tugs at our hearts and calls loudly for our help.

[1] Refugees from the east, fleeing the advancing Russians.

We have everything ready to take in these people; all available space is made free. Soft straw mounds are everywhere. Scrubbed wash boilers are ready for the preparation of meals. Full milk cans are in place. The coal supply for the central heating system will last through the year. Bernhard[2] is almost always in Mestlin[3]. This winter he is training a new supervisor. To drive back and forth from Mestlin would be too dangerous because of the low flying airplane attacks. I am thankful that Bernhard has provided me with potatoes and free milk. My household has other supplies. The poor homeless people should have things better now. They endured such indescribable hardships.

[2] Helene’s husband, Bernhard Philipp Berckemeyer – the owner of Groß Thurow, Gross Thurow or Thurow.

[3] Bernhard had another (leased) farm in Mestlin.

Supervisor Lüneburg and I walk toward the sad looking wagon train. The fine-boned East Prussian horses that are pulling the wagons are so thin – they are like skeletons. We are happy that we have plenty of hay and oats. With limbs stiff from the cold, the men climb from the wagons. Herr Lüneburg tends to stabling and feeding the horses. I go to help the mothers, the children, the old and the sick from the wagons. I cannot speak of the wretchedness and misery that I see – it must be dealt with! They are so happy when they hear that they should all come into the house where they will be fed hot milk soup which is already being prepared for them. The mothers have yet to leave the wagons so I take the many children in tow. I estimate that there are eighty small frozen creatures. I felt a little like the Pied Piper of Hamlin as I started for the house with my long train of children in tow. Only my intention is not the same (as his was).

As we enter the house, the children draw deep breaths as the warmth of the house engulfs them. I rub the cold, blue limbs of the youngest children. They are immediately laid on their beds since the room is now full to capacity. The children are served soup and bread. The mothers brought the bowls and spoons from the wagons. The babies’ bottles are filled. The refugees, who withstood the cold thus far, have terrible memories of the injustice and misery of their flight. It has left heavy scars. We try to help by serving them tea and gruel. There are many things to worry about! Mrs. Bobzin has endless amounts of cooking to do. We can communicate easily with each other via the food elevator that runs from the kitchen to the dining room above[4].

[4] The kitchen was in the lower level, at the end of the house facing the lake. That is also where the laundry was located. – A. von Storch

It is late by the time everyone is fed and each has found a place to sleep. I hear a lot of coughing from the children; there are many feverish faces. After examination it is established that the red rash on their backs is measles. Quickly we prepare a quarantine room so that not all the others will be infected. As I arrived back at the entrance hallway (Diele) I found the doorway blocked. A man, disoriented and extremely agitated, apparently from his terrible fear, has blocked the doorway. He raves and refuses to leave his self-appointed station by the door. By way of the path past the steps, I bring two sleeping powders which he would take only with a glass of grog. This was apparently a drink familiar to him and common to his home region. The sleeping powders did their job and the next morning, before he was fully awake, he was taken to hospital.

There is peace in the Thurow entrance hallway which accommodates the old and sick. In the main hall (Saal), one sees the look of disbelief in the eyes of the forerunners, as they look upon the crowded mass of exhausted mothers and children. I make my last round of inspection, bringing with me hot milk and honey. The coughing can be heard in all the rooms. The smile of a grateful child, already half in a dream, accompanies me as I go to my late night’s rest on this unforgettable February 1, 1945.

April 1, 1945

After the first experience, we now know that every evening when the tower clock strikes six, more refugees will arrive. They come – the long grey ‘caterpillars’ (wagons) of the trek (Treck) [5]. They bring to us their grief, their hunger and their homesickness.

[5] Treck in English is trek – defined as an organized migration (by wagon), a wagon train, or travel by a group.

We help where we can but one despairs – seeing so much grief. The refugees tell us of their flight over the lagoon where the Russians were always at their heels. Due to the melt having begun, the ice was thin. People with wagons and horses sank. Mothers knew that their children were in these wagons. Babies froze and were left by the wayside. They must flee ever faster. The thoroughbred mares cannot stand such strain and endurance. By the hundreds, they abort their foals and collapse. Anyone who knows the East Prussian countrymen knows that they have a great love for their horses and heartfelt feeling for their misery.

Very sick people are brought to us. They ask us, “Please let us die here”. We have prepared beds for them in the administrative building (Wirtschafthaus) because the guest rooms in the estate house are still occupied by the first arrivals, even though several have moved in together in order to make room for friends and relatives. Now refugees arrive from their estates in Pomerania and Eastern Mecklenburg. They often arrive with all their employees (Leuten[6]). There are as many as ten or twelve big wagons in a trek – often there is no space for the horses in the barns. We must now ration the oats. The wheel maker (Rademacher [7]) repairs the damage to the many wagons that break down.

[6] Estate or farm owners referred to their staff or employees as Leute (Leuten) which, in English, means ‘people’.

[7] Rademacher = Wheel maker / Woodcarver / Carpenter. Most large farms employed a full time resident wood carver. This person was able to do all the woodwork needed – making wagons, wheels, windows, doors, cabinets, drawers, flag posts, etc. The same was true for blacksmiths. They made horseshoes, wheel rims, rakes, spades, and repair parts for broken machinery. – A. von Storch

Thurow is known as the ‘change-over camp’ . The treks are now allowed to stay with us for only one or two nights. Further destinations and directions are given by the headquarters in Ratzeburg.

We now had to adopt a more hardened philosophy[8]. (Nun heisst es für uns: “Landgraf, werde hart!”)

[8] My grandparents were overwhelmed with the flood of humanity and could no longer manage to provide free food and shelter for the hundreds of additional newcomers. There was no time for tears or sentimentality – a job had to be done. Conflicts among the refugees had to be adjudicated, priorities had to be set, lost persons had to be found and tough judgements had to be made. Grandmother revealed a huge sense of compassion for the crowds of hapless strangers. She revealed strength of character and an unselfish sense of duty to her fellow man. She demonstrated organizational skills and boldness (later even ordering the Allied occupation forces to perform certain humanitarian duties). Women of that time showed remarkable survival skills and endurance – truly unsung heroes but few remember their accomplishments. – A. von Storch

It is not easy to send the exhausted people further after such a short rest, especially when they believed that they had found a home with us – but the next two or three hundred people are already waiting to camp here.

It continues like this for two months. Both big wash boilers are filled with potatoes and will be cooked and ready at 6 o’clock sharp. We now have the Pomeranians in the line. A real Pomeranian needs noodles to keep him happy – they have the bacon for the noodles in their wagon.

From the group of women, I always pick a pair of big girls and give them the job of directing the ‘waterworks’ (signs show the direction). This plan proved worthwhile. The little ones return with freshly washed and braided hair. They are much livelier than before – often singing and playing. A family that has already had an endless struggle is now ill but this is where I enter the picture – with medicine for their condition. We are no longer shaken by this misery since, how could it be different? The straw for the beds is changed often. Although I encountered little creatures (presumably lice) only three times – they were quickly forced to ‘pick up their tents and leave’.

April 15, 1945

Quartering (billeting) the refugees continues as more arrive. A motor vehicle repair shop is opened in Thurow. All space that can be used is cleaned out. Signs indicate the purpose of the various rooms. The main hall (Saal) is the office. The entrance hall becomes known as the mess hall. The administration building is the common cooking area for the soldiers.

Bernhard is back from Mestlin where he and Gisa[9] had similar experiences (with refugees). Every evening we invite a different group of (German) officers to our dining table. They do not let the depression that grips all of us, affect them. Before leaving, Major Voss holds a general get-together in the main hall. We are also invited. The cooperation and manner of the troops is exemplary.

[9] Bernhard and Helene’s daughter, Gisela Behm née Berckemeyer.

In spite of the warm comradery that the officers show their people, each soldier kicks his heels together and stands at attention when he is addressed. Each is ready for his assignment. I try to attend to drinks for everyone but the contents of the wine cellar were long ago buried and the beer is no longer drinkable – but my apple juice is still plentiful.

The performance begins with Löweschen ballads with violins and piano. Then there are recitals and then all join in the singing of folksongs. That ‘Erika’ and ‘Annemarie’ [10] are not missing from the sing-along, attests to the emotional state of our guests.

[10] These are the titles of two German patriotic folksongs. They were supporting the troops by singing them.

For us it is not always easy to remain strong. We know that this is the end of the comradeship of the German military life. In the Thurow hall, (main hall, Saal) under ‘the eyes of our ancestors’[11], we witness the end of the old Prussian spirit.

[11] The Saal was the room in Thurow where portraits of the Berckemeyer ancestors hung.

At daybreak, with strong handshakes and a signal to depart, the soldiers left the yard in an endless line of Lkw’s[12]. For two weeks these vehicles had been parked in the driveway and camouflaged with fir boughs. The linden trees were not yet out in leaf. From every direction, vehicles were brought for repairs. This attracted low flying enemy aircraft. From early in the day until dark, six aircraft circled over the yard. Wounded and dead horses were brought to us. For the first ‘unknown soldiers’, we created a small cemetery in the mill forest behind the garden. Soon one becomes accustomed to this danger. It takes all of Bernhard’s inner strength to go to his appointments. The garden waits, unattended. Even though the ‘small silver birds’ (enemy low fliers) fly overhead, old Stephan and I do not let it bother us as we go about our necessary tasks. Always the care of the fields is more important to a farmer than his own safety is. Is it different for anyone else? And will it not always be like this?

[12] Lkw is Lastkraftwagon, a cargo truck made by Mercedes Benz.

It tears at one’s heart to speak of what follows. Not only do the troops (disbanded German soldiers) stream in on us – no – the ideals and principles with which we were raised and which were clearly laid out for us by our parents and by the generations before, have collapsed. The principles and ideals that we held steadfastly to – ‘Be faithful to the oath’ – it is no longer!

In throngs, they fill the house and yard, these poor troops – hurried, leaderless, almost weapon-less, poorly united, without courage and without hope – ‘Woes to the conquered’ awaits us.

During these weeks I had experiences that affected me personally and I would like to insert them now. Several names come to mind and I would like to mention them here. From the endless treks of friends and acquaintances: the family Hertz-Crien came with every last member of their family, Mrs. von Tiessenhausen with four of the Freir-family children, Rampaus with a large ‘pastor’ family (Pastorenfamilie), the old Bredow’s-Zaschendorf on their little springless (rough riding) box cart. Lacking supplies or possessions they are thankful for a bag of whole wheat from the granary loft. They spoke of this later and said that is what kept them alive.

How easy it is to please people during these times. In reality our hands are so empty – we cannot give them back their homes.

Some of the refugees stayed several weeks and slept in their wagons inside the barn. The Estonians fled early on, in fear of the approaching Russians. For the same reason, many treks were in a hurry to cross the Elbe-Trave canal. Often they came back because the bridges were closed. This happened to Mrs. von Heintze and our five von Storch[13] grandchildren and to Mrs. von Buddenbruck and her three children. Gabriele[14] and four of her children stayed with us for awhile. (Ingeborg, Heidi and Klaus were sent out ahead of time.) She wanted to go back to Leezen one more time – to be on her estate and stand by her people (employees). But time runs short – soon we must send this small flock over the canal. The Russians have advanced as far as Rostock. For them, it is just a ‘cat’s leap’ through tiny Mecklenburg.

[13] Bernard and Helene’s daughter, Ellen, married Detlev von Storch. They had five children and owned a farm at Parchow. Mrs. von Heintze and the five children fled from Parchow just before the Russian troops arrived. Ellen von Storch had died in 1942. Alexander von Storch is the second son.

[14] Bernhard and Helene’s daughter, Gabrriele Berckemeyer née Berckemeyer. She married Hans Berckemeyer, a distant cousin of Bernhard’s. They owned an estate at Leezen.

We are greatly concerned about Gisela. We had heard from fleeing (German) army officers who arrived here from Mestlin[15], that Gisa had refused their offer to give her and the (two) boys a ride to Thurow. She wanted to remain there (in Mestlin), until she could trek as a group with all her people (employees). This (trekking) had been prohibited until the very last moment by the (Nazi) Party bureaucrats[16]. As a result, she was still in Mestlin when the Russians approached[17]. Just before the Russians’ arrival, and before they got drunk and ravaged the fully occupied residences like wild animals, Gisela miraculously escaped.

[15] Shortly before the end of WW II, Bernhard had handed Mestlin over to his youngest daughter, Gisela.

[16] A permit was required for trekking. – A. von Storch

[17] The arrival of the Russians was often sudden and unexpected because the Nazis suppressed news reports of an unfavorable nature. Russian troops arrived in waves; the first troops usually stayed for only a few hours and then fought on. They were subsequently replaced by occupiers. – A. von Storch

A female friend of Gisela’s from a school in Heiligengrabe[18] came through Mestlin on April 30th, studied the situation and in early morning light took Gisela and the children through the back door and through the churchyard. At great speed, they escaped in her wagon. The whole way they had the feeling that they were being followed by a (Nazi) Party vehicle.

[18] Heiligengrabe is a small town in eastern Mecklenburg. All of Bernhard and Helene’s daughters were educated there in a very strict religious boarding school, called a Stift.– A. von Storch

During this trip, this courageous ‘country child’ sat in the saddle and set spurs to her four horses. Hats off to such daring!

Just before Schwerin, a bridge collapsed under them but that did not deter her, and on May 1st they arrived in Thurow.

I will never forget the feeling of relief that overtook us when Gisela arrived. We had already heard that our pilots had seen the Russians on a march to Goldberg.

There was only one question: “When will they arrive here?” Over and over it was said that the Canal was the Russians’ final goal for a break-through. Hans (Gisela’s son, Hans Behm) beamed – after one year’s absence he was finally seeing his home, Thurow, again. Quickly he sought out his special places and friends. He was jubilant over old toys. But after a short rest, Gisa’s journey had to continue. We grandparents each held this happy little lad on our laps. Then the journey was ready to start. The contents of Blücher’s[19] little wagon was loaded onto a big rubber-tired wagon. These supplies which we had been looking after in Thurow are for Gisa’s flight. The four reliable horses were hitched up and the wiry little ‘Countess’ once again was in the saddle. Thus they disappeared into the dark, gloomy night. The only light came in flashes, like lightening from the bombs that the unerring, low flying planes dropped.

[19] Blücher is the name of a famous Mecklenburg family. – A. von Storch

We both stand by the door – around us a swarm of refugees. They are full of the bleakest predictions. Our heartfelt prayers accompany their nocturnal departure. Our children are safer in God’s hands than in the fists of the Russians.

The next day, both daughters (Gabriele and Gisela) and their children are safe. In friendship, they have been taken in by the Jansens in Steinhorst. Years earlier, the Jansens had apprenticed our son, Dietz (Dietrich) in preparation for his career in farming. They will stay there until July and then they will travel to the old, original Berckemeyer farm near Lengerich (in Westphalia)[20].

[20] Alex von Storch was one of the children who participated in this two hundred mile journey.

May 2, 1945

Glittering light is reflected from the surface of the Goldensee[21] – we rejoice in Mother Nature’s beauty and thank God for His goodness. The leaves flutter and the nightingale sings in the nearby bushes. The candle-like blooms are out on the chestnut trees, as if trying to beam luck and peace into our uneasy hearts.

[21] Goldensee (Golden Lake) was a small lake on the Groß Thurow property.

But how does it look in reality? The Thurow house is teeming with fleeing troops, Lkw’s roar, wounded ask for our help … What will the next hours bring? Which of the three enemy powers[22] will hold onto their occupied areas?

[22] British, American or Russian.

Suddenly through the chaos, an endless line of General Wlassow’s[23] troops arrive – individually, but in marching formation – armed to the teeth. They have Slavic faces and an evil eye. They march along the water avenue (Wasserallee[24]) toward Dutzow. Our people learn that they plan to entrench themselves on Thurow’s boundary (thus at our garden’s edge). Single rounds of shots are fired; low flyers roar; smoke and pillars of fire are all around.

[23] General Vlasov or Vlassov (in German, Wlassow.) General Wlassow’s army was composed of anti-Soviet Russians fighting on the German side (with the Wehrmacht) in the hope of freeing Russia (from Communism).

[24] Wasseralle was a small lane or road that ran along the Goldensee.

A young captain (a resident of Munich) who had been quartered here offered his services as a negotiator with the English. He would drive to Dutzow which the English have already occupied. A white sheet was draped over the hood of his vehicle as a sign of surrender. In a few moments, he roars down the water avenue. Our greatest hopes for success accompany him. Will he arrive in time? Will the fierce Wlassow troops demolish our beautiful Thurow grounds?

Minutes seem like hours. He raises the white sheet and two British negotiators arrive.

Short negotiations take place under the chestnut tree that our ancestors planted over one hundred years ago – surrounded by cheery cushions of flowers in the rock garden, their vivid colours facing the blue May sky.

Bernhard and I are present at all the talks. They listen to our words.

The weapons will be silent. Our beloved Thurow is saved from what, earlier, appeared to be definite destruction.

About what follows now, I do not wish to write many words. It was bitterly hard to endure the disarming of all (German) officers and their men.

The confiscated bayonets lie in rows on the oak bench in the rock garden – like tired warriors, but still in formation. The ground is covered with steel helmets; military belts hung from all the branches.

It is good that there isn’t time to think. The wounded and exhausted want to be cared for. Because of all that has happened, a young lad cries quietly to himself. The tension is broken when suddenly a young anti-aircraft soldier announces, “Madam (Frau Chefin), we have a monstrous hunger”. Laughter rings out – what a relief for all of us.

Everyone offers to help – to fetch and peel potatoes, to carry water and firewood. A forage wagon brings canned goods – a meal is prepared and is very gratefully received. As far as the eye can see, are seated men – on all the gathered-up garden benches and even on the bare dirt. When one glanced over the gathering, one could see on many a young face, relief that the horror was over and they could go home to their mothers.

But we still do not know who will occupy Thurow. Could it be the Russians? The two British left in a German officer’s vehicle. Before the captain left, he noticed a foot bag (Fußsack[25]) and threw it out of the vehicle’s window, smiling at me, “We are no robbers”. But it appears that he thought the vehicle was rightfully his!

[25] Fußsack is a foot bag – for warming one’s feet when travelling in cold weather.

Since our brave little captain had returned to his unit without leaving his address, I will save this foot sack as a remembrance of the day peace came to Thurow.

Many of the disarmed (German soldiers) had snuck away, hoping to return home. The poor men! Soon they will be apprehended at the next checkpoint.

Left behind are several Lkw’s loaded with huge stacks of paper documents with pre-printed military forms. Soon they are scattered over the whole yard – like freshly fallen snow, one would think. The bread wagon still has some bread. It is overrun by Poles. I see to it that the distribution is fair and even. At the end of the water avenue, a food wagon bound for the sick bay, has broken down. The driver upon seeing the entrenchments, fled. One of our resourceful men discovered the wagon which was loaded with high quality food items – like coffee, canned goods, etc. With hand-drawn wagons and empty sacks, a pilgrimage begins. Even the refugees staying in our barns, participate in large numbers. I watch the hustle and bustle from a distance – it is not possible to intervene; the greed is too great! Perhaps it is hunger that drives these people but, as always, those who need it the least are the greediest – a living illustration for the words of Schiller[26] “Then women become hyenas” (“Da werden Weiber zu Hyanen”).

[26] Johann Christoph Friedrich von Schiller (1759–1805) was a foremost German dramatist and a major figure in German literature. Schiller also wrote poetry and essays.

Soon everything is emptied and wheelbarrows quickly disappeared through our garden gate. Only a torn-open sack remained on this eventful site of prior passions. My investigation results in about a hundred weight (100 kg) of ground pepper. Everyone was stunned at the sight of so much spice. I want to leave the sack to its fate and the incoming thunderstorm but on second thought, I realize that I can use it in my mass food production. Then I see two of our refugee boys with their tiny pony wagon coming toward me. They are vigorous little fellows who had driven this wagon themselves during their flight here, albeit in their mother’s tracks. I called to them and the three of us managed to carry this ‘strange’ load to the house. I could give pepper to many people to spice up their insipid daily soup for many days to come. The village women come when their animals are to be butchered, asking for portions of pepper (‘Päpper’[27]). I wonder if today, after four years, one can again get pepper in the German fatherland. Nevertheless, I have enough pepper to last me during my entire life.

[27] Päpper is the low-German word for pepper. Helene uses low-German expressions from time to time. – A. von Storch

May 3, 1945

It is natural that this day will see more worries and unrest. Reports come from the neighbouring estates that the Polish harvesters and the Russian prisoners went wild and created havoc. They emptied out the smoke chambers, robbed the estate houses and raged around with weapons. Our consciences are clear in regard to the welfare of our workers. We gave them whatever was possible – during and after the occupation. We managed, after much arguing with the authorities, to acquire work clothes for them and sugar which was at a premium, was divided evenly among them. On Christmas Eve, each Polish child received a delightful gift.

What the foreign workers received on their food ration cards was modest but who knows about the ‘underground’ channels of incitement. We decided to slaughter our best young ox and divide it among them. The restrictions have been lifted during these upsetting times. Fate comes to our aid. – Because of all the commotion, the shepherd had not noticed that seven sheep had gotten into the new clover and suddenly became ‘fat’. They had to be slaughtered and these well-fed, plump, tasty animals were brought into my kitchen where we happily divided them among the Poles. Each person waited patiently in the line up until their turn came. Happily they took their roasts in hand. One young Polish woman strokes my arm and says, “Madam, good, good” (“Frau Gnädige[28], gut, gut”).

[28] Genädige Frau means Madam. Because the Polish woman does not know German very well, she transposes the two words. Gnädige Frau was the title that employees often used when addressing the patron farmer’s wife. Most farmer’s wives were brought up to care deeply for the welfare of their employees (certainly, there were exceptions) and deserved the description ‘gnädig’, meaning compassionate, kind, forgiving, good-hearted, generous. My father and grandfather were often addressed as ‘Der Herr’, and their teenage sons would be called ‘die jungen Herren’. Workers were usually addressed by their last name, without the title ‘Herr’. – A. von Storch

Our captured Russians are to leave on the next day. As a preventive measure, I ask if I should give them bacon as provisions. With a sly chuckle came the answer, “Thank you, thank you, we already procured that from the farmer”.

We are proud of our experiences with our foreign workers during these times of murder and mayhem.

Many embittered Polish folk and released prisoners make the area unsafe. A black vehicle with a fire-red Soviet star on the door drives up. With failing voice, I said, “Bernhard, they are here”. We take a deep breath but quickly recover from our fright when we realize that the Soviet star was a joke.

Soon the first American vehicles stop by the door. Approximately ten armed men storm into the house. Stammering in German, they ask, “Where are weapons, where revolver?” – apparently the only hastily learned German they know.

Our gun cabinet is emptied out and even the ancient old weapons from our great-grandparents time are taken, even though it is no longer possible to get ammunition for them. Binoculars and pen holders are also popular items.

To understand what follows, I must first tell what previously happened. Since our move from Weisin[29] years earlier, we were never able to find Bernhard’s (WW I) war revolver. When the danger from the Russians moved ever closer, Bernhard acquired another revolver. We both took lessons from an expert on handling the gun, so as to be prepared for a final emergency. It was hidden so well that during the tumult of the past weeks, we had totally forgotten about it.

[29] They leased a farm at Weisin for 32 years. In 1936 Bernhard bought Groß Thurow and they moved there in 1939 when the lease on Weisin expired.

The gun raid begins and whatever did not open easily was broken. Bernhard works downstairs with one group and I do likewise upstairs. Suddenly I hear excited voices – the forgotten (lost) Weisin revolver was found by rummaging hands under old letters in Bernhard’s desk. With red faces they say to us innocent ones, “And you said you don’t have any more arms?” Bernhard does not try to justify his position – they would not believe his story, nor is his command of English very good. I see that they are primitive folk and under some pretext, take them into the dining room and to the liquor cabinet. Just the sight of the liquor calms them down. They are allowed to choose. I had to sit at the table with them and touch glasses with the last of our good Curaçao. Their toast: “Pappa lies, Mamma is good!”

In a calm manner, I tell them, in English, the revolver story. The rage subsides but the search goes on.

If only we could remember where we had hidden the second revolver, we would give it to them but everything goes so breathlessly fast that we cannot discuss with each other as to what would be the correct thing to do. If we should contradict each other, we are lost.

My linen closet was rummaged through three times. A pair of fine leather gloves was found and promptly disappeared into a uniform pocket. “They belonged to my son”, I quietly said[30]. Upon this, he returned the gloves to the closet and closed the door. The search was over.

[30] Bernhard and Helene lost two sons in the war – Hans-Hubertus and Dietrich.

That evening we found the revolver. It was in that very same closet – nearly visible, it lay under the loose laundry. It is possible that it was only a coincidence or shall we believe in a guardian angel?

As dusk falls and all the soldiers are gone, the two of us take a quiet walk and a small shovel to a bush on the outer edge of the park[31]. But I am not happy with this spot. The next day I wander through the crowd of (American) occupying army soldiers. On my arm, I carry a basket full of flowers. For the supposedly light contents, the basket is quite heavy. Deep down in the reeds, in a quiet spot by the lake (Goldensee), our last weapon found its grave.

[31] The Thurow property had approximately ten acres of park. – A. von Storch

May 4, 1945 and thereafter

With a feeling of relief, we awaken in the morning, happy that the Russians are far away and it is the Americans who occupy this area. The Russians have firmly established themselves on the Schwerin-Wismar line. The control checks[32] have ended and now we will be left in peace. There will be tranquility in the country and we can once again resume our work undisturbed.

[32] Control checks conducted by the Allies in search of weapons. – A. von Storch

A radiant Sunday arrived at our beloved Thurow which has withstood many perils. This is to become a ‘day of the Lord’ – a day of thanks and peace. First, a bath in the beautiful green tiled bathroom[33] – one would like to dress festively to celebrate this great day of freedom.

[33] In 1939, Bernhard renovated and modernized the Thurow house. The tiled bathroom was one of these improvements.

Suddenly from in front of the house, comes the penetrating sound of a horn. Bernhard, still in his bathrobe, runs down the stairs. The interpreter orders, “All Germans leave the house immediately, it will be taken over” (by the Americans). We have half an hour’s time! All the refugees escape to the barns and stables. I will not want to claim that they left as empty handed as when they arrived. We free up two little rooms in the administration building for Lüneburgs and us. On such short notice, we can bundle together only the absolute essentials. For the time being, we are not allowed to enter the house, the kitchen or the storage room. That I took the basket of keys as a necessary reassurance is illusory. We later found that all hiding places, cabinets, dressers and chests were broken and rummaged through, and some items were stolen.

Mrs. Lüneburg cooks for all of us in the little room where she, her husband and two children live. The entrance to this room is through our room.

Our five little ‘von Storchs’ from Parchow and four others arrive back from Steinhorst with equipment in two large trek wagons. The danger from the Russians has temporarily subsided. They told terrible stories about the thievery by the Poles and how, by the Thurow Lake (Goldensee) they were pursued by Poles with drawn revolvers and how they had knives thrown at them. This danger was confirmed when the next day, the corpse of a refugee was brought to us. We bury him in a quiet spot in the mill forest. No authorities, no police! – These days no one asks questions about the ‘wheres and whys’ of a death.

For a long time the von Storchs must find shelter in the barn.

The heat from the very hot days penetrates our little south-facing room under the asphalt tar-paper roof. The flies are bothersome and hard to bear. Nearby, in my laundry room ‘mother and child’ (mothers and their children) are crowded but accommodated. For eight nights, with clenched teeth and as good a demeanour as we can muster; we bear the nocturnal shouting, the smells, the pressures and responsibility for the horrible disorder. How long will our strength last?

The coffee house (Kaffeehütte) stands in front of our window – close and inviting. In the main attic are big cardboard sheets. An energetic person hauled them down and past the occupiers. Hilperts, a helpful Pomeranian farmer family, built us a small chamber where we can spend the nights in quiet solitude. When the sun sets, we were forced to go to bed[34]. As far as I can remember, we did not try to collect the sunlight in sacks and carry it indoors as did the legendary Schildburgers[35].

[34] There was no electricity (no lights) in the coffee house.

[35] Schildbürgern are legendary people who can best be described as ‘clumsy buffoons’. One legend says that they tried to transport sunlight in sacks, into their dark rooms. – A. von Storch

Soon we were allowed to use some rooms in the main house because it had been impossible for Bernhard to manage the business without the use of his desk, its contents, the telephone, etc. But in the evenings we must return, in our bathrobes, to our ‘Albergo’[36]. It continued like this for weeks. If we rise early, we can enjoy the sight of sleeping Yankees on every sofa of our house.

[36] Albergo is a southern-European hotel/restaurant chain – apparently renowned for good service. Helene seems to say, with tongue in cheek, that her nightly abode in the coffee house was not luxurious. – A. von Storch

A sergeant (American) who is friendly to us manages to create order around him. This relieves us of several responsibilities. He also has the refugees clean up all the paper that had earlier been strewn about.

After the raid on countless inflatable boats belonging to the German military (Wehrmacht), a few (boats) remain. Many had already been cut up and converted into aprons. The sergeant allowed two to be left behind for our von Storch grandchildren to play with. For a long time this was their entire joy. Then the Americans left. We got over the loss of the things that they took from the broken containers but they took six tubes out of the radios that the sergeant had returned to us – this is hard! Now we are totally cut off from world news and events. “In two days the Russians will be here” – are their ‘reassuring’ parting words.

But the American vehicles roar onward across the yard directly over the circular lawn (Rondell), into the middle of the rhododendrons which are now at their best. It has always been the nicest sight of the year. The cream coloured house blends into the pale sea of lilac blossoms. The upkeep of the park, I leave to the refugees who receive eggs and the like for their efforts – always hoping that all those who live in the chaos and Bohemian world, might find a resting place and a well ordered life again. We also hope that our property will be handled more carefully by the refugees and others, if it appears cherished and precious.

Thus the ongoing daily activities continue in our garden. The refugees in the neighbourhood coin the phrase ‘The Thurow Spa Park’. For them it is an attraction – all benches are always occupied. Between the benches, the Americans lounge or they trot around the corners on sweat-drenched Trakehner[37] horses. The large von Storch family has settled down in the kitchen area of the Thurow house where they can now conduct themselves as they please. We had a small stove placed near Bernhard’s bedroom. Mrs. Hilpert cares for us in an unselfish fashion. In this time of infinite uncertainties, we sent Mrs. Bobzin and the girls to their relatives. In the event that the Russians do come, they do not wish to be identified (labelled) as ‘profiteering, arrogant Junkers[38]’. Soon a new place is found for the community kitchen. The refugees enjoy living in my nice new chicken shed. The laying boxes become laundry and food cupboards. The chicken excrement boards (Kotbretter) – forgive the use of this harsh word – are scrubbed shiny clean and become the most useful washstands.

[37] Trakehner is a type of Prussian riding horse.

[38] ‘Junker’ is a derogatory term used by the Communists to describe the despised class of large land owners. – A. von Storch

Led by a captain with a leg prosthesis, a number of (German) officers’ wives who had fled together, settle cheerfully into these permanent quarters. One of these women, a Mrs. Kule, offered to manage the refugee’s kitchen. This was a big relief for me. After I replaced her only flimsy purple dress with several laundry dresses made from a blue and white chequered bed cover, she swings the cook spoon with expertise and dedication. In the morning, at a pre-arranged time, I delegate everything to her, confident that I can depend on her and that the people will have it good.

It makes us very happy that my sixteen asparagus beds (now four years old) yield such a rich harvest. The treks that, once again arrive daily, bring many relatives and acquaintances from the old homeland. They experienced the Russian invasion and tell of gruesome events. The news seeps through about the poor people who shot themselves and their families as the Russians advanced. We hear of those that were sacrificed and fell victim to the mutinous soldier’s guns. How many veterans, friends and dear acquaintances are among them?

Can we bear so much grief and heartache? Won’t we collapse? Being very healthy people, we are thankful for our high limit of endurance. Many of the poor people, who did not have this same level of endurance and because of extreme anxiety, chose suicide. They were not the worst – rather, they were often the most compassionate among our brothers and sisters.

Our daily work helps us get through each day. Bernhard is happy that he can finally move around unhindered and attend to his business, even though the absence of the Poles and the prisoners was readily apparent. Tired auxiliary members of the (former German) anti-aircraft force and exhausted soldiers were no farm labour substitutes. These people come from very diverse backgrounds and occupations and they longed to go home. The pitiful turnips, our foundation for winter feed, are drowning in weeds. Later the (allied) ‘supreme commander’ helps us: “We direct” (the able-bodied workers to do the work) is posted in large letters and that order is carried out.

Clover grows in abundance so Bernhard sets aside a field for grazing all the refugee’s horses. People come, even from the neighbourhood, with their scythes because it is not possible to get oats in the grazed-off Lauenburg[39] land.

[39] Lauenburg was the province in which, at that time, Thurow was located.

When the refugees from Dutzow and from Klein-Thurow[40] arrive at my door with empty bowls and spoons, the Boss[41] issues an order; As far as the young people are concerned, only those working in Thurow should be fed. So each noon and evening, I give out stamped tokens. The old folk and children receive long-term vouchers. Every mealtime there is a long line up at our laundry room[42] door. Over one hundred people are fed daily. Many an ox (speak old cow – sprich alte Kuh) ended up in the wash kettle (to be cooked). Are we allowed to do this? You can keep a secret![43]

[40] Klein-Thurow (‘small Thurow’) was a small village located near the estate of Groß-Thurow.

[41] The Boss would be Bernhard or his deputy (the Statthalter). – A. von Storch

[42] The laundry room had become the kitchen used to feed the multitudes. Laundry machines were unknown at that time. Therefore laundries contained a huge, coal-fired, built-in kettle (as well as scrub boards, tables, pails, baskets, and hand-cranked wringers). Laundries were usually in the cellar. A Plettzimmer (ironing room) was generally in an upstairs room with better lighting. – A. von Storch

[43] Food was officially still rationed.

Bread was brought from a central dispensing station in Thurow for all of Thurow’s people (those living in the village, the house, the barns and the stables). Ration cards issued by the occupying forces are required for this bread. Mrs. Buddenbruck takes on the job of issuing out the bread. On weekends, butter packets were distributed by the boss (Bernhard) himself, because occasionally this task required rigorous and energetic enforcement. Three additional stoves were installed in the administrative building. All ‘travelers’ can prepare their traditional meals there with the resources they brought along in the nooks and crannies of their wagons. Do you have any idea how many requests we get; from morning to night? We hardly have time to blink before another swarm arrives with more requests. Explanations are not necessary. For the poorest, everything is missing – from nails to toothache medicine.

In my notes of these weeks, I find these words: “The little granddaughters come running as soon as they see me but usually there is only enough time to give their hair a quick stroke or to go with them to the baby chickens or to the strawberry patch”. Since there is no school or lessons, the young boys savor every moment of their freedom but we are concerned – they could run wild. Their unsupervised wanderings could bring them to harm, especially when their greatest interest is in the munitions which lie everywhere. I am happy each night when I know that they are safe in their beds. They always come to us before bed for a glass of juice and to tell us of their happiest experiences of the day.

In my sphere of influence, I decide that anyone needing fruit and vegetables should appear, mornings at 9 o’clock, in the garden; followed by any requests for other household supplies from the meat cellar, medicine cabinet, etc. The wishes of those arriving late will not be considered. It is a matter of course that everything is given freely because, with what did we earn (the luxury) of not being one of those who must stand at other people’s doors?

Soon everything is organized and I can, as in the old times, once again join Bernhard for a drive to the fields. We share the joy of seeing the bountiful harvest that the fields promise. Now, after nearly ten years and Bernhard’s tireless work plus a favourable spring, Thurow has been brought to its highest level of productivity. This is confirmed by comparing with our records of other years.

Once again an enemy lies in wait at the gates – typhoid dysentery brought in by the Russian soldiers. Due to the lack of proper hygiene and overcrowding, it has increased tenfold. The picture was the same on all other estates. It is fortunate that among the refugees there are doctors – thus each village has its own doctor but how can they help without medical supplies? Our doctor is the competent Dr. Gerhard from Dutzow. He swears by chamomile tea for dysentery – the same remedy used in grandmother Lene’s time. “If only I had one pound of this! I would give thousands (money) for it.”, was the comment the doctor made with a sigh. Every June 20th, as is our tradition, we gather great amounts of chamomile. I took a big bag of it to the doctor – he was so happy. He can use his ‘thousands’ in other ways. Tirelessly he tended to all the Thurow people who were sick – whether in a normal bed, a cluttered covered wagon or in a dark corner of the barn. Our grandchildren have been hit very hard with this illness and we are greatly concerned. I was one of the last to become ill. During the high fever, I see life as if through a haze. Bernhard’s words wake me from my exhausted state – “You must take Armgard (von Storch) or she will die in our hands”. Together we soon became well again. The spark of life is probably strong in both of us. Armgard has also inherited a sense of mischief from me. When we go hand in hand through the village, the people say, “The girl is exactly like Mrs. Berckemeyer” (“De Lütt is Fru Berckemeyer – ganz und goar”[44]). It often seems to me as though this youngest grandchild was snatched straight out of the children’s room in Groß Brütz (die Brützer Kinderstube[45]).

[44] This is low-German.

[45] Helene often mentions “Die Brützer Kinderstube” in her stories. It refers to her childhood on the estate/farm in Groß Brütz and the method by which she was raised. – A. von Storch

Again we hear rumours of a Russian break-through. Lüneburgs leave and the von Storch caravan gets on its way under the leadership of Mr. von Bruddenbruck. They will travel across the canal. The Kule era (Kule-Ära[46]) in the administration building also comes to an end. Inspector and Mrs. Giese, with the support and assistance of Gerda Kabelmacher, work and live there. My little chambermaid came back from the Goldensee. Now a shuttle service for our mealtimes is possible. There are often things to laugh about. The owner of a dog kennel managed to get her seventeen dogs out from under the Russians. We must provide high class accommodations for these creatures with the bearded snouts. To guard them, she personally spends the nights in front of the kennel door at Mother Grün’s place. A horse that has been killed provides the nutrition for the dogs. The meat is cut into strips and hung on the clothes line to flutter and dry. I am in a hurry to pass but first I must admire the dogs. “Yes, very cute”, I say. I feel that this is enough of an ovation. Now her words shower down on me like a hailstorm, “Cute, you say about my wonderful pedigreed dogs? Cute? Picture perfect is what they are, standing there”. The entire ancestry of these dogs comes spewing forth. It sounds to me that their origins could be traced back to Noah’s Ark. From now on I make a wide detour whenever the vegetable garden calls me.

[46] Mrs. Kule was one of the fleeing (German) officer’s wives who had taken over the management of the refugee’s kitchen.

The two boys who helped me with the sack of pepper are growing into little monsters. At midnight they come crashing up the stairs. With anger and with a rate of speed achieved only by the sudden awakening from a deep night’s sleep, Bernhard is in the corridor and administers slaps that land on unsuspecting ears. Unexpected was the subdued gratitude expressed by their powerless mother on the following morning.

In the meantime, without much fanfare, we become British[47]. We have been lucky so far in keeping the (British) occupying soldiers away from the house. It is enough to tell them, “The water isn’t good in this house. You see, all of us are sick”. Because of their fear of germs, it is not hard for us to negotiate and to give the impression of exhaustion from sickness. Unintimidated by the talk of sickness, the energetic adjutant to a colonel, steps forward and through an interpreter, he triumphantly announces, “We bring our water with us”. I am standing by an open window and am an involuntary witness to the following remarks from the colonel, “Yes indeed, a nice water place. Look at the flowers and the lawn we will have for our play[48]”. Then emphatically, this ‘deluxe edition’ from an aide, “And the house, isn’t it comfortable?”. We are doomed. Thurow, because of her beauty and well-groomed appearance has dug her own grave.

[47] In May 1945, the Allies declared all of the province of Mecklenburg as part of the Soviet Occupation Zone. Thurow was located in the province of Lauenburg at that time, not Mecklenburg, and so it now belonged in the British Occupation Zone. Thurow was however, located very near the Mecklenburg border.

[48] These words were written in English by Helene. ‘Water place’ may refer to the presence of the lake.

With polite but energetic tone, the aide tells us that the house must be vacated by all civilians. These are the regulations. A total of eighty officers and men will be moving in. “That’s my death” are the only words that I can weakly utter. The nights in the heat, the ten crying babies and the billions of stable flies, prey on my sanity. The cardboard wall around the coffee hut, fell victim to a thunderstorm.

Human compassion appears on the face of the Almighty. The adjutant gives a short command, “Come let us look for the rooms”. We hesitate in fearful expectation but are happy when the three upstairs rooms in the east wing, with a small bathroom and a balcony, are to be for our use. In overflowing joy at this unexpected good fortune, I say a heartfelt “Thank you very much” and reach for the colonel’s hand. He quickly put his hand behind his back. Can you imagine what it was like for me to be so insulted in my own house? Later I find out that it is a regulation that they are not allowed to exchange handshakes with any Germans. So of course, he could not ignore this rule in front of his subordinates. Never again did I offer my hand to an officer of the occupying forces – not even after the fraternization laws were lifted and they (the Allies) began to solicit our goodwill.

Our (this British) colonel and his large staff remained in Thurow for many weeks. I did not carry a grudge towards him. He requested that I have my gardener fill the vases once a week. I replied, “I myself am the gardener and I will gladly do this”. Now I have a reason to go at any time, through our chambers and to give the waiter (? from the kitchen staff) an occasional sign. As soon as the fruit ripens (strawberries, cherries, etc.), I place a big bowl of it on the round table in the main hall – as a sign of hospitality. The officers never fail to seek me out and give their thanks. It shows that even in hostile times, the civilized life style of good manners has not died.

In all the neighbourhood estates, vegetables and fruit are being requisitioned, but our garden seems to be sacred to them. The troops do not climb over hedges and fences. We were allowed to choose the furnishings for our three rooms – so it became comfortable and cozy in this, our involuntary old-person’s section[49].

[49] Traditionally, the east wing of the house was where the retiring generation lived when the next generation moved into the main part of the house and took over the management of Thurow.

Many memories are attached to this end of the house. During Bernhard’s childhood, his beloved aunt Agnes and Miss Karthaus lived in these rooms. Later they became the bedrooms of his parents and still later it became Gisa’s little domain. Our Hänner (Gisela’s son, Hans Behm) was born here[50] during the war with only his Omama (grandmother) there to receive him. This was not the first time for me. A grandmother who is also a countrywoman, has to be able to do everything. The grief and misery rages on, but we also had some joy. A son, Hertz, whose fate is unknown, causes his mother great concern – we were able to show him the way to her (presumably they found the son). Later his father arrives – this was for us the saddest sight we had in this period of time. As we were making our nightly rounds, we see coming down the road toward us, an exhausted and faltering figure in a torn uniform. The man appeared to be totally finished. Bernhard recognizes him – his friend Gustav Hertz. A few months earlier, he was still with us – a solid figure to his troops. He carried the title ‘Reserve Colonel’, with pride. At almost sixty, the passionate love of his fatherland prompted him to volunteer. Shoulder stripes and Knight’s cross were hanging down and trodden into the dirt – just like his courage to face life. At Thurow, he wants to inquire about his family and if the news is bad, he wishes to end his life. We are so happy to be able to tell him that his wife and all four sons are alive. We drive him to our house where we encourage, nurse and clothe him. After a few days he is well enough to move to his family in Steinhorst. He is not the only one – we have helped others regain their strength and their will to live.

[50] Hans Christian Behm, born on August 21, 1940, was the last Berckemeyer descendant to be born in Groß Thurow.

Three Weisin residents (two Dunkers and one Maykopf), former playmates of our boys, arrive. They are happy to see familiar faces and have accommodations and farm work made available to them. Another guest is Prime Minister Stratmann from Schwerin. He wants to go to Hamburg to see if he can have all of Meckenburg freed from the Russians and to establish it as a food source for the Hamburg-British base. He arrives back with little hope of this happening. His shiny government vehicle and smartly dressed chauffeur seem oddly out of place during this time of neglect. Marliese and Barbara Hartwig are shattered when they hear that their parents are now in the hands of the Russians. They learn that their parents had been seen living in a forest camp by Schwerin but had then turned back to Daschow.

All strangers who were brought to our house were under guard and were there for short terms only. Except for Professor G. and his wife. They were settled in the granary attic, with our furniture. They have the special good will of the colonel. Both were great riders and show-offs. They were allowed to choose ten Prussian riding horses from Perlin. For Bernhard – another burden. For me – another new and daily joy, to observe these masterfully ridden thoroughbred animals in the riding arena or in front of my window, in the early morning. Soon the colonel joins in. One is always fearful that the little graceful ‘cats’ (horses) will collapse under his colossal size. One is also reminded of the prairie cowboy because of the English style of riding. The G.’s wish to have close contact with us. He was a medicine man (quack) at the Königsberg University and offers Bernhard injections for his arthritis. He ‘coincidentally’ happens to have six left. My gullible husband allows himself to be beguiled. Every other night the Königsberg ‘Great One’ arrives with all his therapeutic equipment. A bowl of strawberries and a dug-up bottle of Mosel wine hold us together. His Amazone (woman show-jumper – his wife), the better rider of the two, was also present once and the topic of horses dominates the conversation – so it is not obvious that politics and past events are not spoken about. He does not take our suggestion that he report to the Kieler University. We ‘clueless’ ones do not notice anything and it does not occur to us, that for our hospitality, we will later pay bitterly. Suffice it here to say only this – the injections and their ‘coincidence’ has to be considered ‘false information’.

Gabriele and Gisela, with two children, arrived from Steinhorst in a panel truck. It was their first visit but they could stay for only a few hours. There was great joy in seeing each other again and there was no end to the stories we had to tell each other.

When Gabriele, with Helga and Hans (two of her children), came again on the 30th of June, she encountered a most critical day. We were with them, and the numerous members of the Dr. Eberhard family, in the vegetable garden where we had gone to fill their baskets with fruits. A rider arrives at the fence with the news that the rest of Mecklenburg was being readied for a Russian take-over. The transfer would happen at six o’clock. The Eberhards rush away in their pony wagon – they can still get themselves and their belongings out of Dutzow and into the British zone. The Steinhorst vehicle that Gabriele came in is in Mecklenburg (the town) and will not pick her up again until six o’clock. That, along with Gabriele and the children, we go peacefully to the black cherry tree in the lake garden (Seegarten – the garden by the Goldensee), is an indication of how accustomed we are to this kind of ‘shotgun news’. It is like living on the edge of a volcano – we are hardened to it. Hans is positioned in the yard as a look-out. Shortly before six o’clock his voice rings out like fanfare, “A vehicle is coming!” Quickly they (Gabriele and the children) climb into a vehicle which is filled with the wounded. They had escaped from the Gadebusch hospital before the Russian invasion and on the way, had knelt beside the road and ministered to the wounded. The vehicle speeds along and with some exceptions, arrived safely.

The next morning the Russian border cuts our harmless water avenue (Wasserallee) in two. The village and the barns are emptied. The closeness of the Russian Star is frightening. So far they have not dared to encroach on the house. From the cattle enclosure located far from the house, a full milk can is picked up daily by the Russians and returned empty in the evening. When the dairy foreman demanded payment he was told, “The farmer (Bernhard) should come for it himself”. But since the ‘farmer does not come himself’, this free-for-all activity goes on unhindered, unpaid and for a long time. It does not look this peaceful at all of the borders. We took a young nurse in our car and delivered her to a trek that was traveling in the direction that she wanted to go. She was half sick with fear but a hundred cigarettes helped to calm her a little.

The Dutzow Castle is stuffed full with casual or day workers. The cottages however, are taken over by the Russians. “We Bolshevists do not live in castles.” – Also a pride! (Auch ein Stolz!)

I find the following records (in my notebook) about these days: “Many dark figures come sneaking into Thurow; they had fled in the thirteenth hour, hiding in ditches and hedge rows. Women with unkempt hair have blackened their faces in the hopes of displeasing (making themselves undesirable to) the Russians. When they hear that the danger is past and they can stay here overnight undisturbed, they break into hysterical laughter.

An amputee limped on one leg (hopped is a better word) from Schwerin to here, a naked, unwashed child (sitting) on clover hay – that is what I saw while I sat on the sun bench on the evening of July 1st. Bernhard is once again making room in the barn for more fleeing crowds – they will surely come searching for a safe haven. During the last days of June, Ernst Albrecht[51] wants to bring his wife back from Hohenholz. A few (German) generals are on board – he wants to take them to a safe place. He will come through Thurow but his lucky star holds him at his parents-in-law. Soon word arrives that everything in the Brütz house has been devastated.

[51] Ernst Albrecht Bock, Helene’s brother

July 8, 1945

The first and only meeting of the high commanders from West and East takes place in Groß Thurow. Everything had already been prepared (for this meeting) a few days earlier when the ‘Njet’ (negative) Russians had arrived. But the ‘Russkies’ (Iwan) declared that they would be ready (for the meeting) on the 8th of July. Breathlessly, thorough preparations begin. The marking of fences and benches is done with canvas strips which extend around the lawn in front of the house. Plants that were transplanted from the bright begonia beds are completely unmotivated to take root. (They wither on the very next day.) The (British) colonel grabs the lawnmower – whether for sport or out of nervousness remains a mystery. As well as an abundance of flowers, I donate three capons which are welcomed for a special festive treat. The waiter asks for silver, especially cutlery for fish. (Is the handling and essentiality of these items familiar to each guest?) By the way, I am happy that the organization and directing of this feast is not my responsibility.

Innumerable tanks drive up with many honour guards to hoist both flags in the middle of the circular flower bed. So now the Soviet Star also flutters over Thurow. About thirty British and Russian officers, generals, field marshals and a tall, thin Scottish general in a kilt roar in – all in elite German vehicles. Our (British) colonel, in a sort of a trot, ran to meet them at the entrance – (apparently a British honour reception?). A Scottish bag pipe plays the national anthem, followed by inspection of the troops and the presenting of huge bouquets of flowers. The military parties disappear through the house door, under our Berckemeyer coat of arms.

We have experienced the making of history, but what sad history for our Fatherland. It was from behind bushes that we discreetly observed everything because the colonel had personally asked us not to let on that we lived in the house – which we understood in light of this important and official business.

Quietly we creep upstairs while they are completely captivated by the ten course meal. We hear, through the open main hall door and windows, how the mood and noise has accelerated – because of the consumption of so much wine. Finally the Allies’ braying laughter gets out of control. Above all, the kilt of the Scottish general arouses an abusive merriment – “A woman, a woman”, resounds in broken English.

For musical entertainment, the bag pipe plays ‘Lili Marleen’[52] almost exclusively – probably by request but perhaps it was his complete repertoire. Eight officers (all Russian) equipped with Leica (cameras) photograph the group by the main hall door, by the garden and several other places. This is how our Thurow will be shown in Russian cinemas and newspapers – a horrifying thought.

[52] Perhaps the most popular song during World War II. The English version (Lilli Marlene) or the original German (Lili Marleen) became the unofficial anthem of the foot soldiers of both forces in the war.

Even without the difference in uniforms, one could recognize the nationalities. One is slim and sporty with lively facial expressions. The others – different . . .

While their spirits are high, they drive away. Once again there is quiet in old Thurow. The colonel falls exhausted into an armchair on the terrace. Quietly I go through the expanse of rubble that they left in our house. I step on shredded bouquets of flowers; stumble over empty glasses, bottles and broken glass. The chaos can no longer be managed. Our valuable Meisin and Sevres china is spread around the house. We find some of it even outside. Club chairs are left outside in the rain. Distinct scratches on the mahogany furniture are noticeable – some scratches had (previously) been made by the Americans who used the tables as footstools.

It does not upset me anymore. In my thoughts, I have written everything off and when, once again at a later time, we should get these items back, I will consider it a gift. One’s heart does not belong to material things. Those who once thought it did, are learning now. I never considered myself to be one of those who value the material things of life more than life’s content.

Finally I have time to drive to Steinhorst. A big rubber-tired wagon is loaded with necessary things for the children. Things that they should take to Westphalia[53] because the unrest in the east does not stop. I sit in a little one-horse cart being pulled behind the wagon, so that I will have something to drive back in. The joy of the children is so cute – joy over two milk cans containing berries and joy over the beloved teddy bear (‘Brummbär‘). This teddy bear has excited the second generation now, with his growling and has already received his third new fur hide for Christmas. They are so happy to see their Omi (grandmother). ‘The lap and the hands, right and left, are always besieged and disputed over’ as written in the annals. We sleep over and under and mixed up. Anything goes when one is on the trek.

[53] Westphalia (Westfalen) is the province (in the far western side of Germany) where the ‘Birkenhof’ was located near Lengerich. The ‘Birkenhof’ was the original Berckemeyer farm, possibly dating as far back as 1383 and is still owned by Berckemeyers today. They spell their name Berkemeier.

I have more stories in reserve for those who would like to hear more of that eventful summer. I would like to tell about a ‘warning shot’ that happened somewhat earlier.

A peaceful morning finds us at the breakfast table. A menacing knocking on the door and two men in uniforms unfamiliar to us, stand uninvited in the middle of the room. Without giving a reason they inquire, “Wes Nam’, wes Stand und Art” (“What name, what position and of what type.”) Only the handcuffs are missing – everything else is there. “Immediately come to the colonel!”

I follow this dubious order. In the entrance hall stands (Professor) G.’s[54] driver with arms raised, already swaying and with his face strained and contorted. (This driver had brought the colonel’s horse to the door each day.) A few people with submachine guns at the ready surround him. The way we heard it later was that they were an armed Secret Service Squad. Bernhard was taken alone into the consulting room.

[54] Professor G. was the medicine man or quack mentioned earlier in this document.

But I hear a strange voice questioning – in German. “How long have you known Professor G.? How did it happen that you had a leading SS man, invited by you and housed here for weeks? Speak the truth or it will cost you dearly.”

In this tone, the conversation lasts one hour. (Left unmentioned is the fact that the colonel rode with them (Professor G. and his wife), allowed the family to be fed and demanded that we meet their requests.)[55]

[55] Presumably, Helene is referring to the fact that G. was really the British colonel’s friend while he was at Thurow – not Helene and Bernhard’s friend.

I am sitting on hot coals, idle among these distrustful, suspicious ‘weapon carriers’ standing opposite the prisoner who is near collapse. Finally the door opens and Bernhard is dismissed because the questioning went nowhere.

We learn that G. was Forster’s[56] right hand man. He personally attended to SS[57] matters and with his well known ‘syringe’ carried out their terrible deeds. A cold shiver runs up my spine. How easily he could have made an ‘accidental’ mistake while he was deceiving us. He was taken away to an unknown destination. After months, his wife had still not heard from or about him. This did not hinder her in continuing the equestrian sport in the colonel’s royal stables – even as soon as they left Thurow.

[56] Albert Forster was ‘Nazi Governor’ of the district Danzig-West Prussia.

[57] Nazi SS = Schutzstaffelor Protection Squad

We learned to be on the alert. Whoever wants to hide his Nazi misdeeds under our wings is urged to leave our premises and go to where the eyes of the law are less watchful and property expropriation is not expected.

From the beginning we feared that the interpreter’s sympathies lay with the enemy and that he initiated the whole matter. Perhaps because of past bad experiences, he had reasons for this attitude but that is not our fault. It could also be because of a quiet outrage that the colonel bypasses him and turns directly to us. He calls himself ‘Mr. Ashley’ but unmistakably, he is ‘Herr Ascher’ from Frankfurt. All signs point in that direction – even his Hessen dialect which is evident when he relaxes his guard. He probably learned from an Englishman, who spoke broken German, the phrase “Pay attention”, because every sentence directed at us begins with these words. It is when he suddenly utters the words (in a Frankfurt dialect), “The guy has dirt on his cane”, that we understand and are doubly watchful. He rummaged through our bookcases from top to bottom without finding ‘ a hook to hang us on’. His secret mission leads him to the quarters in the barn which belongs to the ‘Attraction’ (presumably a woman of ill repute). He arranges new accommodations for her and confers the title of nobility on her. I never found out how long that title was valid but it was in effect during her weeks in Thurow.

It was a spectacle without equal to watch G. help that little hunchbacked man into the saddle of a Trakehner (horse). (G. apparently wanted to promote goodwill with him.) Once in the saddle, this little man expected us to admire his riding skills.

Suddenly in mid July the headquarters were moved (from Thurow) to Lütjensee. The reason is evident. Close by our house, encompassing the whole width of the park, the bright canvas strip is laid out to mark the interzone border. The immediate proximity of their Russian allies is frightening to the (British) high commanders. They take Bernhard’s beautiful inherited desk[58] – the same one the colonel used when he was in Thurow. Later after several visits to Lütjensee and a hard fight, we managed to get it back. When the troops departed, the following mindset prevailed: “Take whatever you want but do not steal”. But where was the limit here? They just took what they did not rob. Many mattresses and beds are tossed into the Lkw’s. The house is cleaned out of cooking utensils and dinnerware. No mirror is left on the walls, no wash basins are left – none . . . it is not possible to list it all. The few short hours without the occupying army are used to equip the two small violet rooms near the bathroom, in order that we may offer a quiet spot to any wanderer whose last hope is Thurow.

[58] This mahogany desk was purchased by Bernhard’s great grandfather, Bernhard Philipp Berckemeyer when he bought Groß Thurow in 1798. It is now in Gabriele’s son, Hans Hubertus Berckemeyer’s possession.

A (British) police squadron (officers and seventy men), move in. Uncouth conduct prevails. Jazz tunes rang out half the night and from every room there is incoherent shouting, laughter and charging about on the carpets. The departed staff had been interested only in matched sets of silverware and dishes as well as book cabinets. Without our knowledge, they had taken linen and cutlery from boxes which had been left by unknown treks and had been stored in our attic. Thus we could determine neither the initials (of the owners), nor the number of points in their crowns[59]. Now a lot of work was done. After the Americans had left (some time before this) we had all locks in the house changed. Now they have all been broken again. We are powerless since we are forbidden to enter the occupied house.

[59] Helene is referring to the social status of some refugees. Lower ranked nobles had five points in their crown and higher ranked nobles had nine. – A. von Storch (Presumably, these identifying marks would have been on some of the items that had been taken out of the boxes.)

So that the troops would not fraternize with the Russians, the whole contingent was rotated out (changed) every fourteen days. In spite of that, we often see and hear drunken, shouting Russians leaving our dining room in the dark of night.

We were unable to observe what was taken from cupboards and drawers when the exchange of troops took place. It appeared to me that the company leader could be influenced. I had occasion to get some pieces (of furniture); with something like these words, “You see we are old people and we haven’t any comfortable chair”. And so it was that the desired grandfather chair was returned to our room. One must be little diplomatic. Soon the thievery by the troops became too much for even the English. In every room, then hung a list of furniture that one or another took charge of. For us – nothing more could be attained unless one turned to a little trickery.

Daily a little dog ‘Jacky’ is fed by our door. He had his food served on one of our Meisin china plates (the oldest pattern!). For as long as this little monster honours Thurow with his presence, it is my intention to exchange the Meisin plates for a tin one. We rescued a whole stack of these plates. As you later eat from these brown-striped plates that look like they are almost cracked through, think of little brown Jacky and your grandmother.

Now I will once again let my original notes from the last days in July (often written in telegraph style), do the telling: “The days are again filled with rumours that the Russians have advanced as far as the Elbe river. We are happy when each morning we awaken in what is still British Thurow”. Many important items and valuable files and letters are already in the safekeeping of our ‘Röbchen’[60]. As much of the beautiful old family silverware that would fit into milk cans had already been buried in the spring. We had purposely planted nut trees in the lake garden (Seegarten) so that we could bury the milk cans under them. Word had spread about the methods the Russians used to discover treasures – they probed the ground with steel bars. Bernhard fears for these valuable family heirlooms – perhaps one day they could help the children in an emergency. I prepare myself for the journey to Lauenbrück which is on the other side of the Elbe.[61]

[60] Röbchen is the nickname of a person. – A. von Storch

[61] Presumably to take the buried silver to a safer place.

Bernhard and I travel together as far as Steinhorst in order to visit our daughter and many grandchildren before they start off on their trip to Westphalia. I stayed for two days and, along with Gisa and six grandsons (aged one to fifteen years), I slept on a mattress on the floor. In the early morning there is happy hopping and sliding into Omi’s (grandmother’s) bed. At six o’clock the big boys (Bernd and Alexander von Storch) go to the fields to begin their day of pea picking. Gabriele and Gisa want to take these two with them to Westphalia.

The whole crowd accompanies us to our trek wagon. The passionately loved doll, ‘Friedolin’ is also there. All hands are filled with raisins and plums. Boxes containing sand templates in bright colours are held in anticipation. We hear the happy words, “I am looking forward to our trip because it is then that we will get the sand templates”. Even the turbulent days of the preparation for the move are special for the children. We think, with a quiet smile, “Let me be a child – be a child with me!”

We are thankful to the Jansens (he is the master of Steinhorst) who for so many weeks gave shelter to them and endured the antics of the children. We hope that the same kind of friendliness awaits them in the land of the red earth (at the ‘Birkenhof’ in Westphalia). We send Inspector Giese and his wife along to help and protect them against danger. (The Gieses had replaced Mr. and Mrs. Buhlert in Thurow.)

During my travel two days before the departure of the children, the horses which I had acquired in Dutzow a few weeks earlier, ‘denied’ me their services. One notices that the Thurow oat bin has been empty for a long time – whatever was left by the trek horses was eaten by the riding horses.

On every slope the little horses invariably came to a halt. It was only when the coachman, Vorbek, and I took hold of the bridles that they slowly started up the incline. Both the box cart and the little coach are too heavy for these poor starving wretches who must exist on green fodder only.

I make a hasty decision to take the road through Lütjensee. I presented myself (there) before our (British) high commanding staff after first having had no success with the lower ranking authorities. Through persuasion and persistence, I receive the following: Seven Zentner (seven hundred kilograms) oats for the children’s trip, three Zentner (three hundred kilograms) for me and a spare horse for my wagon – as far as Volksdorf. The horses that are in the worst condition will rest here in the paddock and be exchanged again tomorrow.

The military staff has moved into a charmingly furnished weekend house belonging to rich people from Hamburg. With a motor boat on the lake, riding horses in the stalls and the Russians far away, they seem to be content.